How doctors take healthcare to people who would otherwise struggle to access it

Nearly 400km south of Raipur, the capital of Chhattisgarh, lies a town called Bijapur. It is the kind of town that now survives only as a memory for many people living in big cities. There are no malls or theatres, and power cuts are frequent.

“It’s like going 20 years back in time,” says Poorva Kher, a graduate of the Goa Medical College, who spent two months in Bijapur with Doctors Without Borders/Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF) for her first job. “It’s the kind of setting I wanted to work in as a doctor. You won’t get this experience anywhere else.”

Not an ordinary clinic

The town is part of Chhattisgarh’s southernmost Bijapur district, the site of a longstanding low-intensity conflict. People living in far-flung villages of the district find it extremely difficult to access healthcare. In order to reach them, MSF conducts mobile clinics every week.

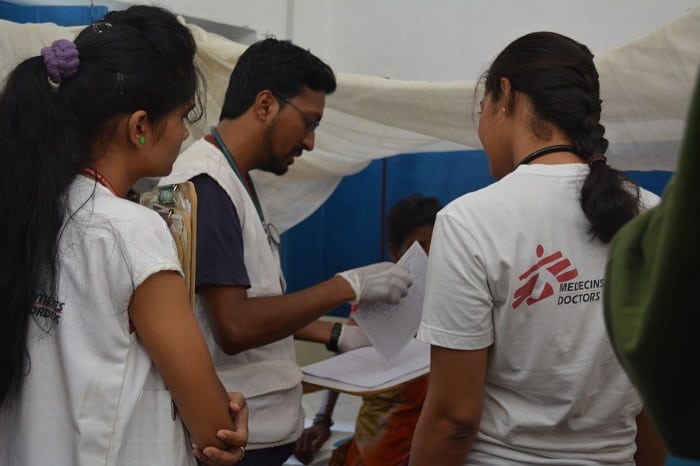

If your idea of a clinic includes a permanent structure, state-of-the-art equipment and the smell of disinfectant, MSF’s mobile clinics will change that. The clinics are set up in villages at least an hour away from Bijapur, where there is no electricity, no phone network and very often no transport. MSF teams set off early in the morning with everything needed to run a clinic – weighing scales, malaria kits, medicines – loaded into bags. There are no roads but when even the trusty MSF vehicles won’t go all the way, our teams walk to reach the clinic location.

“Our clinics are most often under a tree. We create a place for registration, nurses, doctors, laboratory technicians and drug dispensers. We don’t have any table or chair, we sit on the floor on a tarp sheet. Or we take a charpai from a house nearby and start the clinic,” says Manoj Sarma, an emergency physician from Assam who worked with MSF in Bijapur recently.

Treating people cut off from healthcare

The clinics run from morning to late afternoon, during which time MSF teams provide free primary healthcare, including immunisation, malaria, respiratory infections, pneumonia and skin diseases among others. The clinics offer a separate area for women to address needs in reproductive health, where group and individual sessions are conducted on topics such as hygiene, care of newborns and sexually transmitted infections.

“At our mobile clinics, you can see how cut off people are from healthcare. They come to us for even headaches and body aches, because they can’t get a paracetamol. So what is basic medication for us is a luxury there,” Poorva observes.

A number of ailments seen by MSF teams are preventable, and MSF’s health education team plays an important role at the clinics in making people aware of common diseases, their symptoms and preventive measures. For instance, they demonstrate the use of mosquito nets to prevent malaria and explain the importance of hygiene and handwashing to prevent skin diseases.

Patients that require hospitalisation are referred by MSF to secondary health facilities in either Bijapur town or Jagdalpur. From reimbursing their cost of travel to covering the medical expenses, our teams support the patient throughout their treatment.

Dr Sahithi, a doctor from Hyderabad, remembers a newborn with lower respiratory tract infection. The child had to be taken to a medical facility four hours away, in Jagdalpur. “All the way, for all of the four hours we had to keep performing CPR. The child finally made it, and it made me feel so good. I remember the kid and his mother still. She hadn’t named the child yet and asked me to give him a name. I named him Hanumaiah, after my grandfather,” she says proudly.

Until recently, MSF also operated a 15-bed Mother and Child Health Centre (MCHC) in Bijapur town where medical teams provided reproductive, paediatric and TB care. In 2016, 309 babies were delivered and over 5,000 antenatal consultations were carried out at the MCHC. With these facilities now available in the district hospital, MSF closed the MCHC earlier this year.

But people living beyond the periphery of the town continue to have extremely limited options in healthcare. So doctors like Manoj, Poorva and Sahithi will continue to go the extra mile, to take medical care to people who need it most.