New outbreak declared in Equateur province

On 1 June 2020, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) declared its eleventh Ebola outbreak since records began, following the revelation of new cases of Ebola in Equateur province, northwestern DRC. Less than two years since the last outbreak of the disease ended in Equateur province – and while the country is waiting to officially declare the tenth outbreak, in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, over – authorities have reported over a dozen people with either confirmed or suspected cases in the city of Mbandaka and surrounding area.

On 9 June, WHO announced that there is no link between the tenth outbreak and the eleventh outbreak; they also established that the virus in the new outbreak is distinct from that which circulated in Equateur province during the country’s ninth outbreak.

MSF response to eleventh outbreak

Following the declaration of the eleventh Ebola virus outbreak in DRC by the Ministry of Health (MoH) on 1 June, MSF is sending an exploratory mission to Mbandaka to assess the situation and identify the MoH’s needs in terms of treatment.

For now, it is unclear whether the confirmed and suspected Ebola cases will remain isolated or whether we will soon face a major Ebola outbreak. Any MSF intervention will be decided upon the information that will be collected by the fact-finding mission in the coming days, and the operational capacities of MSF in relation to our other ongoing activities in DRC.

Response mechanisms to the Ebola epidemic are still in place in the east of the country, where we have trained medical teams and strengthened prevention and treatment measures in support of the public health system.

Summary – tenth outbreak

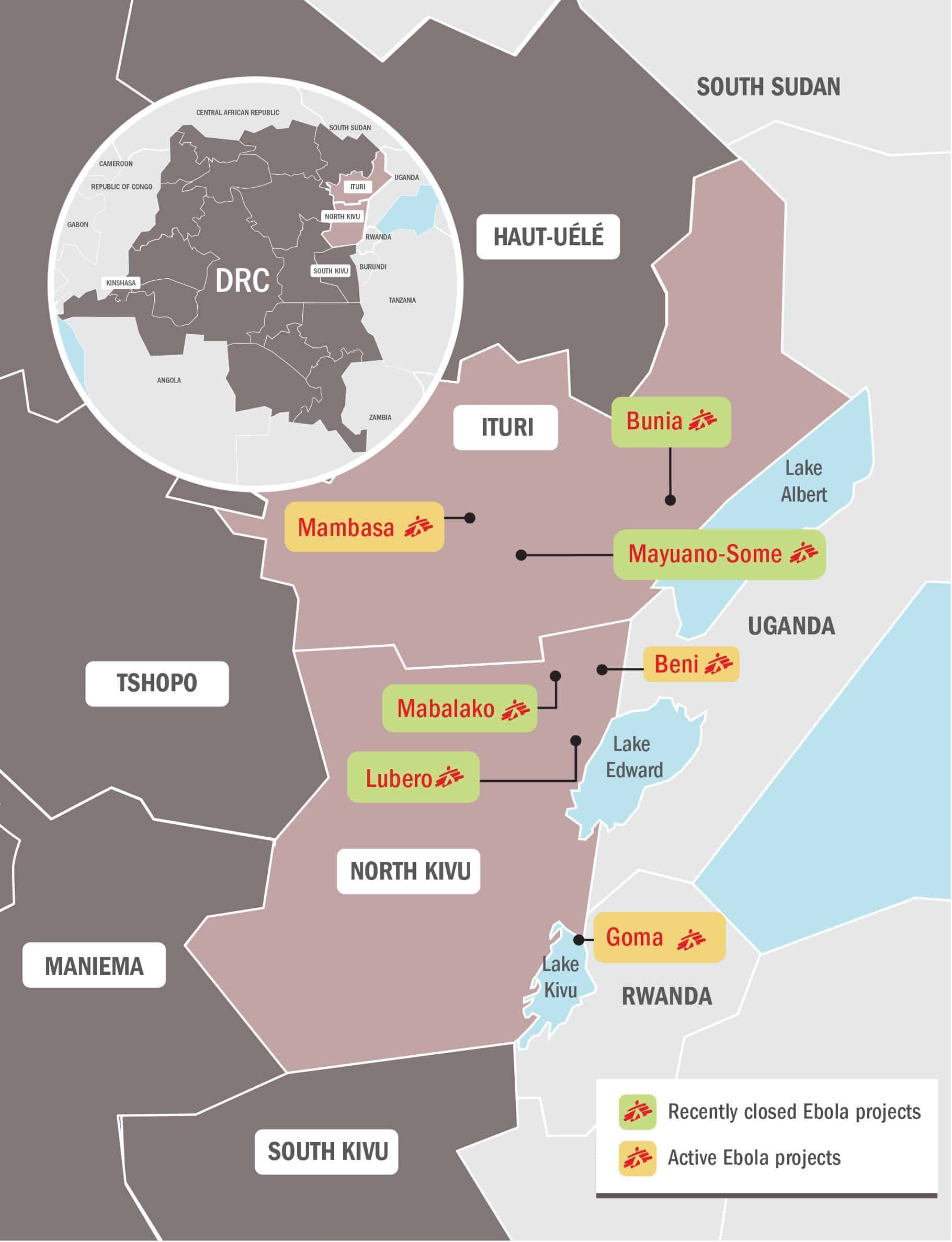

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) declared their tenth outbreak of Ebola in 40 years on 1 August 2018. The outbreak is centred in the northeast of the country, in North Kivu and Ituri provinces; cases have also been reported in South Kivu. With the number of cases having surpassed 3,000, it is now by far the country’s largest-ever Ebola outbreak. It is also the second-biggest Ebola epidemic ever recorded, behind the West Africa outbreak of 2014-2016.

During the first eight months of the epidemic, until March 2019, more than 1,000 cases of Ebola were reported in the affected region. However, between April and June 2019, this number doubled, with a further 1,000 new cases reported in just those three months. Between early June 2019 and the beginning of August, the number of new cases notified per week was high, and averaged between 75 and 100 each week; it then started slowly declining for the rest of the year.

In 2020, the number of cases recorded per week has declined dramatically, with just a handful of cases recorded throughout January and February. However, on 10 April – just three days before the outbreak was expected to be declared over – a new case was recorded in Beni. Six further cases had been recorded in the same area.

Although the last Ebola patient was discharged from the Beni ETC on 14 May, the outbreak is not yet officially over and there is a continued need for vigilance, especially in the midst of the current coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic.

Latest figures on 10th outbreak – information as of 31 May 2020; figures provided by DRC Ministry of Health via WHO.

At the peak of the outbreak, identifying and monitoring contacts was a significant challenge, with 40 per cent of new Ebola cases having never registered as contacts. Reasons include the movement of people (such as in the case of motorbike taxi drivers), to downright fear in some communities which hinders engagement. In addition, new Ebola patients were confirmed and isolated with an average delay of five days after showing symptoms, during which time they were both infectious to others and missed the benefit of receiving early treatments with a higher chance of survival.

On 11 June 2019, Uganda announced that three people had been positively diagnosed with Ebola, the first cross-border cases since the outbreak began. After several weeks with no recorded cases, the Ugandan government announced a new case on 29 August; the patient, a young girl, sadly died.

On 14 July 2019, the first case of Ebola was confirmed in Goma, the capital of North Kivu, and a city of one million people. The patient, who had travelled from Butembo to Goma, was admitted to the MSF-supported Ebola Treatment Centre in Goma. After confirmation of lab results, the Ministry of Health decided to transfer the patient to Butembo on 15 July, where the patient died the following day. On 30 July, a second person in Goma was diagnosed with Ebola; they died the next day and two more cases were announced.

No new cases have since been recorded in either Uganda or in Goma.

In reaction to the first case found in Goma, on 17 July 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the current Ebola outbreak in DR Congo represents a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

In mid-August, the epidemic spread to neighbouring South Kivu province – becoming the third province in DRC to record cases in this outbreak – when a number of people became sick in Mwenga, 100 kilometres from Bukavu, the capital of the province.

Since November 2019, an upsurge in violence in North Kivu and Ituri provinces has disrupted the provision of care, surveillance, vaccination, contact tracing and other activities of the Ebola response, forcing us to remain extremely vigilant about the resurgence of the disease.

Background of the epidemic

Retrospective investigations point to a possible start of the outbreak back in May 2018 – around the same time as the Equateur outbreak earlier in the year – although the outbreak wasn’t declared until August. There is no connection or link between the two outbreaks.

The delay in the alert and subsequent response can be attributed to several factors, including a breakdown of the surveillance system due to the security context (there are limitations on movement, and access is difficult), and a strike by the health workers of the area which began in May, due to non-payment of salaries.

A person died at home after presenting symptoms of haemorrhagic fever. Family members of that person developed the same symptoms and also died. A joint Ministry of Health/World Health Organization (WHO) investigation on site found six more suspect cases, of which four tested positive. This result led to the declaration of the outbreak.

The national laboratory (INRB) confirmed on 7 August 2018 that the current outbreak is of the Zaire Ebola virus, the most deadly strain and the same one that affected West Africa during the 2014-2016 outbreak. Zaire Ebola was also the virus found in the outbreak in Equateur province, in western DRC earlier in 2018, although a different strain than the one affecting the current outbreak.

First declared in Mangina, a small town of 40,000 people in northern North Kivu province, the epicentre of the outbreak appeared to progressively move towards the south, first to the larger city of Beni, with approximately 400,000 people and the administrative centre of the region. As population movements are very common, the epidemic continued south to the bigger city of Butembo, a trading hub. Nearby Katwa became a new hotspot near the end of 2018 and cases had been found further south, in the Kanya area. Meanwhile, sporadic cases also appeared in neighbouring Ituri province to the north.

Throughout 2019, hotspots of cases would die down, only to flare again weeks or even months later – often after 42 days (twice the 21-day incubation period for the disease) had passed – and often with little or no indication of the chain of transmission. This signifies that surveillance and contact tracing of cases were significant challenges in overcoming this outbreak.

Area

Located in northeastern DRC, North Kivu province is a densely-populated area with approximately 7 million people, of whom more than 1 million are in Goma, the capital, and about 800,000 in Butembo. Despite the rough topography and the bad roads in the region, the population is very mobile.

North Kivu shares a border with Uganda to the east (Beni and Butembo are approximately 100 kilometres from the border). This area sees a lot of trade, but also trafficking, including ‘illegal’ crossings. Some communities live on both sides of the border, meaning that it is quite common for people to cross the border to visit relatives or trade goods at the market on the other side.

The province is also well-known for being an area of conflict for over 25 years, with more than 100 armed groups estimated to be active. Criminal activity, such as kidnappings, are relatively common and skirmishes between armed groups occur regularly across the whole area.

Widespread violence has caused population displacement and made some areas in the region quite difficult to access. While most of the urban areas are relatively less exposed to the conflict, attacks and explosions have nonetheless taken place in Beni, an administrative centre of the region, sometimes imposing limitations on our ability to run our operations.

Cases have also been confirmed in North Kivu’s neighbouring provinces, Ituri to the north and South Kivu.

Existing MSF presence in the area

MSF has had projects in North Kivu since 2006. Today, we have regular projects along the Goma-Beni axe as follows:

- Bambu-Kiribizi: Two teams support local emergency room and paediatric and malnutrition in-patient departments, plus care and treatment of sexual and gender-based violence.

- Rutshuru hospital: MSF withdrew from the hospital at the end of 2017. However, in light of the volatile conditions in the region, we have returned to support emergency room, emergency surgery and paediatric nutrition programmes.

- Goma: HIV programme supporting four medical centres (including access to antiretroviral treatment).

Current situation

Cases of Ebola have been recorded in 29 health zones across three provinces – Ituri, North Kivu and South Kivu – 28 of them in Ituri and North Kivu. In the last 21 days, only Beni has recorded one case, making it the only current active zone of transmission. As of 6 March 2020, Mabalako has not recorded any new cases for 37 days; apart from Mabalako and Beni, all other previously active health zones have passed the 42 day threshold with no cases recorded, twice the incubation period for the disease.

As of 6 March 2020, no cases have been recorded for the last 18 consecutive days. The outbreak will be declared over if no cases are recorded for 42 consecutive days across all health zones.

WHO declared the outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in July 2019; despite the significant downturn in the number of cases, WHO decided to maintain this status at a meeting in mid-February 2020.

We have new tools and improvements in the medical management of this epidemic, compared to previous Ebola epidemics, such as new developmental treatments; a vaccine that has given indications of being effective; Ebola treatment centres are more open and accessible for the families of patients; and provision of a higher level of supportive care. Despite this, there is a 66 per cent case fatality rate in the current outbreak.

At the outbreak’s peak, many people died in the community – either at home or in general healthcare facilities – and nearly half of new confirmed cases could not be traced to an existing contact with Ebola.

COMMUNITY MISTRUST AND ATTACKS ON RESPONDERS

The response to the outbreak has been marked by community mistrust towards the response. This is due to a complicated history and to many different reasons, but include community resentment on the focus on Ebola, when many other diseases continue to claim more lives, such as a severe measles outbreak; and community objections and anger over the presence of security forces surrounding the Ebola response. This mistrust towards the response has led to attacks, including on our Ebola Treatment Centres (ETCs) in Katwa and Butembo in February 2019, which led us to withdraw from running these centres.

The unrest, such as fighting between the army and armed groups in early May 2019, and again in November and December 2019, have at times brought many outbreak response activities to a standstill.

The mistrust and violent attacks against the Ebola response show no signs of abating; as recently as early November 2019, a radio journalist, Papy Mumbere Mahamba, was killed in Lwemba, Ituri province, reportedly for his involvement in the response. There were more than 300 attacks on Ebola health workers recorded in 2019, leaving six dead and 70 wounded.

High levels of insecurity continue to hamper the efforts to control the epidemic and have a negative impact on its evolution: the violence further discourages people from seeking care in Ebola treatment centres, resulting in an increased likelihood of the virus spreading across the healthcare system.

A new offensive of the national security forces against armed groups started at the end of October 2019 in the area around Beni and has continued across North Kivu. The intensifying military operations, and violent attacks by armed groups, has led to both movements of displaced people trying to flee the insecurity (potentially making surveillance and contact tracing even more difficult), and to protests against the military and the UN, including on some health workers in the Ebola response.

A series of attacks on Ebola responders – some of whom were killed – and on infrastructure in Biakato, Ituri province in late November and early December 2019, led us to make the difficult decision to temporarily withdraw our team, before withdrawing completely at the end of the year due to the presence of military and armed security in health centres, which violates MSF principles.

EBOLA IN UGANDA

On 11 June, the Ugandan Ministry of Health and WHO confirmed three people from the same family had tested positive for Ebola in the Kasese district, western Uganda, which borders DRC. The family had travelled over the border into Uganda from DRC. They are the first cross-border cases in the current outbreak.

Two of the people sadly died, while the third person and two other members of the family, showing symptoms consistent with the disease, were repatriated to DRC.

After several weeks with no recorded cases, the Ugandan Ministry of Health announced on 29 August that a new case had been recorded in the country. A young girl, who had travelled from DRC with family, was diagnosed with Ebola and admitted to a treatment centre but unfortunately died the following day. Uganda has not recorded any further cases.

The response to the current outbreak

The DRC Ministry of Health (MoH) is leading the outbreak response, with support from WHO.

MSF believes that Ebola-related activities should be integrated into the existing health care system to improve the proximity of services to the community and ensure the system remains functional during the outbreak. We aim to do this with our own Ebola-related activities wherever possible. This would help identify earlier on suspected cases and could encourage people to seek help more promptly at healthcare posts, clinics and hospitals that they know and trust.

MSF RESPONSE

MSF had been involved in the outbreak response, working with the Ministry of Health, since the declaration of the epidemic on 1 August 2018.

Current activities

In Beni, MSF handed over the Ebola treatment centre (ETC) to the Ministry of Health on 15 April 2020 – in accordance with what had been planned – but we will continue to provide global support to three health centres in Beni for another few weeks. We will also continue health promotion, and raising awareness of the disease and how it should be treated with traditional healers.

In Goma, the ETC in Munigi, on the outskirts of Goma, will be converted into an isolation and treatment centre for suspect and confirmed COVID-19 patients.

Meanwhile, our teams have built a 20-bed multi-epidemic isolation and treatment centre (for both Ebola and other infectious diseases, including coronavirus during the current COVID-19 pandemic) at the Provincial Hospital of North Kivu (HPNK). This permanent structure aims to sustainably reinforce the MoH’s capacity to face potential future outbreaks in the city. MSF has recently trained MoH staff on Ebola case management, infection prevention and control, and sustainable medical supply management in the lead-up to the HPNK multi-epidemic isolation and treatment centre opening.

Previous activities

MSF had been running the following activities in the affected North-Kivu and Ituri provinces up until February 2020:

Goma – North Kivu province

- MSF had been providing medical care to suspected and confirmed cases in the 10-bed ETC in Munigi, on the outskirts of Goma.

- Vaccinated participants who have consented to take part in a clinical trial of a second investigative vaccine, Ad26.ZEBOV/MVA-BN-Filo from Johnson & Johnson.

- We supported emergency preparedness by reinforcing the surveillance system and ensured there is adequate capacity to isolate suspected cases.

Beni and surrounds – North Kivu province

- Managed a 20-bed ETC in Beni and managing and triaged suspect cases in three health centres; this was handed over to the Ministry of Health in April 2020.

- We provided medical care to suspect cases in isolation awaiting test results.

- MSF teams engaged in community and health promotion activities.

- Supported access to free non-Ebola healthcare in multiple hospitals and health centres across Beni.

Mambasa – Ituri province

- Supported five health care facilities, including access to primary and secondary health care

- Health promotion in the community

- Managed basic healthcare centres and transit units in Binase and Salama.

- Managed the surveillance system in the Binase health zone.

- Implemented infection prevention and control in the community and infection prevention support at 12 health centres.

VACCINATION

Unlike the 2014-2016 West Africa Outbreak, there now exists two vaccines against Ebola which are in clinical study phases and are not licenced. One, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine produced by Merck, has been used in a ‘ring’ vaccination strategy since the start of this year. Using this strategy – where the contacts of people diagnosed with Ebola are vaccinated (first-degree contacts), and their contacts (second-degree contacts) in turn are vaccinated – over 250,000 people have been vaccinated up to mid-November 2019.

In mid-November 2019, MSF teams started vaccinating people who had given their consent to participate in a clinical trial of a second investigational vaccine, Ad26.ZEBOV/MVA-BN-Filo, produced by Johnson&Johnson, following an announcement by the Ministry of Health in September.

While vaccination is a good measure designed to prevent the further spread of the disease, use of the vaccines in DRC during the outbreak is not without its challenges:

- The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine requires to be transported in temperatures of around -60C to areas which are remote and often lack adequate roads and infrastructure.

- The new investigational Johnson&Johnson vaccine needs to be given in two doses, 56 days apart – requiring people to be followed up in a context notoriously difficult for follow-up.

- Identifying contacts and their contacts has been extremely challenging, with three-quarters of contacts not able to be traced or followed up to be vaccinated during this outbreak.

- WHO’s approach to managing supplies and eligibility for the vaccine has been opaque, with even some frontline health workers – those who should be the first to get the vaccine – going unvaccinated.

We have urged for a change in vaccination strategy – given the above challenges – to go for a more expanded, geographically targeted approach, rather than the unreliable ring vaccination strategy.

Vaccination

Unlike the 2014-2016 West Africa Outbreak, there now exists two vaccines against Ebola which are in clinical study phases and are not licenced. One, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine produced by Merck, has been used in a ‘ring’ vaccination strategy since the start of this year. Using this strategy – where the contacts of people diagnosed with Ebola are vaccinated (first-degree contacts), and their contacts (second-degree contacts) in turn are vaccinated – over 250,000 people have been vaccinated up to mid-November 2019.

In mid-November 2019, MSF teams started vaccinating people who had given their consent to participate in a clinical trial of a second investigational vaccine, Ad26.ZEBOV/MVA-BN-Filo, produced by Johnson&Johnson, following an announcement by the Ministry of Health in September.

While vaccination is a good measure designed to prevent the further spread of the disease, use of the vaccines in DRC during the outbreak is not without its challenges:

- The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine requires to be transported in temperatures of around -60C to areas which are remote and often lack adequate roads and infrastructure.

- The new investigational Johnson&Johnson vaccine needs to be given in two doses, 56 days apart – requiring people to be followed up in a context notoriously difficult for follow-up.

- Identifying contacts and their contacts has been extremely challenging, with three-quarters of contacts not able to be traced or followed up to be vaccinated during this outbreak.

- WHO’s approach to managing supplies and eligibility for the vaccine has been opaque, with even some frontline health workers – those who should be the first to get the vaccine – going unvaccinated.

We have urged for a change in vaccination strategy – given the above challenges – to go for a more expanded, geographically targeted approach, rather than the unreliable ring vaccination strategy.